Article Type: Evidence Check, Explainer, Peer-reviewed Cross-referencing

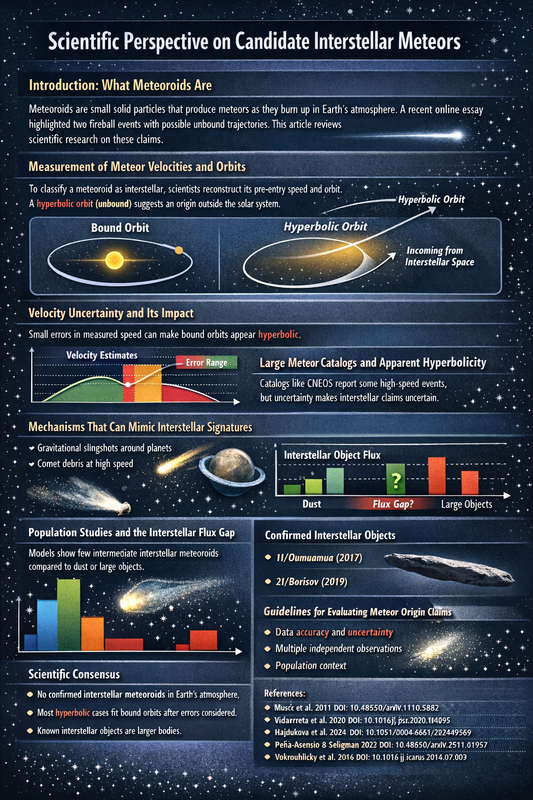

Introduction: What Meteoroids Are

Meteoroids are small solid particles, ranging from sub-millimeter sizes up to meter-scale bodies, that intersect Earth's orbit and produce visible meteors when they ablate in the atmosphere. Determining whether such particles originate inside the Solar System or from interstellar space requires reconstructing their pre-atmospheric orbit.

A recent online essay by Professor Avi Loeb of Harvard University on his Medium Blog highlighted two fireball events with inferred trajectories that could be interpreted as unbound relative to the Sun’s gravity, sparking public interest.

This article reviews current scientific understanding of meteoroid origin classification, the limitations of available data, and peer-reviewed research on claimed interstellar meteor candidates.

Measurement of Meteor Velocities and Orbits

To classify a meteoroid as potentially interstellar, scientists reconstruct its pre-entry velocity, radiant (direction), and orbital elements to determine whether it is bound or unbound to the Sun. A hyperbolic orbit indicates a total orbital energy greater than zero, which may suggest origin outside the Solar System. However, most meteors last only fractions of a second and are measured with ground-based optical and radar systems or space-based sensors, introducing observational uncertainties.

Velocity Uncertainty and Its Impact

Small uncertainties in measured velocity and radiant angle can significantly affect orbital classification. Studies show that trajectories initially computed as hyperbolic can be consistent with bound orbits when realistic measurement uncertainties are included:

- Musci et al., 2011, demonstrated that multi-station optical measurements initially indicated hyperbolic motion, but all events were consistent with bound orbits once uncertainties were accounted for: DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.1110.5882

- Vidaurreta et al., 2020, showed that velocity uncertainties of ~1 km/s can produce spurious hyperbolic solutions for otherwise bound meteoroids: DOI: 10.1016/j.pss.2020.104965

Large Meteor Catalogs and Apparent Hyperbolicity

Large catalogs, such as the Center for Near-Earth Object Studies (CNEOS) database, occasionally report fireballs with computed velocities exceeding Solar System escape speed. A recent article highlighted two such events, but peer-reviewed studies emphasize that without quantified uncertainties, interpreting individual events as interstellar is problematic. Hajduková et al., 2024, analyzed fireball data and concluded that apparent hyperbolic excesses are not definitive evidence of interstellar origin: DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202449569

- "We conclude that there is no evidence in the CNEOS data to confirm or reject the interstellar origin of any of the nominally hyperbolic fireballs in the CNEOS catalog."

Mechanisms That Can Mimic Interstellar Signatures

Even when a meteoroid appears to have a velocity above the Solar System escape speed, several natural mechanisms can produce apparent hyperbolic or high-speed trajectories without requiring an interstellar origin. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for interpreting observational data responsibly.

- Gravitational Scattering by Planets: Close encounters with massive planets, particularly Jupiter or Saturn, can accelerate Solar System meteoroids to velocities that temporarily exceed the Sun's escape speed. These scattered particles may appear hyperbolic if observed near Earth, but they remain part of the Solar System's population. Numerical simulations of meteoroid dynamics show that such scattering events are relatively rare but can generate the highest-velocity meteors detected in catalogs (Vokrouhlický et al., 2014).

- Cometary Debris Streams: Long-period comets shed debris along their orbits, which can include small particles with velocities approaching or slightly exceeding escape velocity relative to the Sun at Earth’s distance. These streams may produce meteors with unusually high apparent heliocentric velocities. However, because the particles originate within the Solar System, they are not interstellar.

- Non-Gravitational Forces: Effects such as radiation pressure, the Yarkovsky effect, or outgassing from cometary bodies can slightly modify meteoroid orbits over time, occasionally giving the appearance of excess velocity when analyzed with limited observational data.

- Measurement System Noise and Aliasing: Instrumental limitations, sensor timing errors, or inaccurate calibration can artificially inflate computed pre-atmospheric velocities. For instance, small errors in velocity or radiant angle measurement can push an orbit across the threshold from bound to hyperbolic. Several studies have shown that a velocity uncertainty of only 1 km/s can produce spurious hyperbolic solutions (Vidaurreta et al., 2020).

- Atmospheric Deceleration Modeling: Meteoroids experience rapid deceleration during atmospheric entry. Inaccurate modeling of this deceleration can affect backward calculations of pre-atmospheric velocity, leading to overestimation of the heliocentric speed.

These mechanisms illustrate why high apparent velocity alone is insufficient to establish an interstellar origin. Each candidate event must be analyzed in the context of Solar System dynamics, measurement uncertainties, and potential observational biases. Peer-reviewed research emphasizes combining rigorous orbit reconstruction, multi-station verification, and consideration of these natural mimics before claiming interstellar provenance for atmospheric meteoroids.

Population Studies and the Interstellar Flux Gap

Models comparing direct measurements of interstellar dust with detections of larger interstellar objects (like 1I/’Oumuamua and 2I/Borisov) indicate a "flux gap," suggesting intermediate-sized interstellar meteoroids (millimeter to meter scale) are extremely rare at Earth: DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.2511.01957

Confirmed Interstellar Objects: A Distinct Category

While no atmospheric meteoroids have been unequivocally identified as interstellar, astronomers have confirmed the existence of larger objects that traverse the Solar System from beyond. These confirmed interstellar objects are distinguished by several key features:

- Hyperbolic Orbits: Interstellar objects are identified through precise orbit determination. A hyperbolic trajectory indicates that the object’s total orbital energy is positive, meaning it is not gravitationally bound to the Sun and will eventually leave the Solar System. Both 1I/’Oumuamua and 2I/Borisov exhibited clear hyperbolic motion verified through multiple independent observations.

- Multiple Independent Observations: Reliable identification of interstellar origin requires repeated detections from different telescopes and observatories. This ensures that initial measurements are not artifacts of a single instrument or dataset. For example, 1I/’Oumuamua was detected by the Pan-STARRS1 telescope and subsequently confirmed with follow-up observations from several other facilities, allowing astronomers to refine its trajectory.

- Well-Characterized Uncertainties: Orbit determinations for interstellar objects include quantified uncertainties in position, velocity, and trajectory parameters. This is critical for distinguishing genuine interstellar objects from Solar System meteoroids that may temporarily appear hyperbolic due to measurement errors or gravitational perturbations.

- Observational Timeframe: Both 1I/’Oumuamua and 2I/Borisov were observed over extended periods as they passed through the inner Solar System. This allowed astronomers to continuously refine orbital models, predict future positions, and confirm hyperbolic paths. Short-lived atmospheric fireballs lack this opportunity for extended monitoring.

- Compositional and Morphological Studies: While small interstellar meteoroids in the atmosphere are typically too brief or small for detailed composition analysis, larger confirmed interstellar objects can be studied spectroscopically. For example, 2I/Borisov showed typical cometary activity, but its trajectory proved it originated outside the Solar System, making it the first confirmed interstellar comet. 1I/’Oumuamua’s unusual shape and non-gravitational acceleration prompted extensive debate, but its interstellar origin is unambiguous based on trajectory.

These characteristics highlight that confirmed interstellar objects are identified using a combination of rigorous orbit analysis, multi-instrument verification, and long-term observation.

They form a distinct category from atmospheric meteoroids, where brief detection and measurement uncertainties make interstellar identification far more challenging. Current research emphasizes that while atmospheric meteoroids may occasionally appear hyperbolic, robust confirmation requires the same meticulous standards applied to larger interstellar objects.

References for further reading on confirmed interstellar objects include:

- Jewitt, D. “Interstellar Objects in the Solar System.” DOI: 10.1146/annurev-astro-091918-104423

- Guzik, P., et al. “2I/Borisov: A Study of the First Interstellar Comet.” DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ab3f13

- Meech, K. J., et al. “A brief visit from a red and extremely elongated interstellar asteroid.” DOI: 10.1038/nature25020

Guidelines for Evaluating Meteor Origin Claims

Claims regarding meteors or fireballs being interstellar in origin are increasingly circulated in online articles and videos. Scientific evaluation requires a structured approach to distinguish between speculative interpretation and robust evidence. Researchers and informed readers should consider the following key guidelines:

- Assess Data Quality and Instrumentation: Determine the source of the velocity and trajectory measurements. High-quality data typically come from multi-station optical networks or radar arrays with known calibration standards. Single-sensor reports, especially from space-based sensors without error reporting, should be treated cautiously. Peer-reviewed studies emphasize that unreported uncertainties can significantly affect orbital reconstruction (Hajduková et al., 2024).

- Examine Uncertainty and Error Margins: Even small errors in pre-atmospheric velocity (fractions of a km/s) or radiant direction (degrees) can change a computed orbit from bound to hyperbolic. Proper scientific analysis accounts for these uncertainties and propagates them through orbital calculations. Claims lacking quantified uncertainties are inherently weak.

- Look for Independent Confirmation: Valid scientific claims typically require multiple, independent observations. For atmospheric meteors, this could mean simultaneous detections by separate optical stations, radar systems, or complementary instruments. Cross-verification reduces the chance of misinterpretation due to sensor anomalies or local measurement errors (Musci et al., 2011).

- Compare Against Known Populations: Contextualizing the event with the distribution of Solar System meteoroids helps identify anomalies versus expected behavior. Large catalog studies show that many meteors initially appearing hyperbolic fall within bounds of Solar System populations once uncertainties are applied. Extreme velocities alone do not confirm extrasolar origin.

- Evaluate Physical Evidence: In rare cases, recovered meteorite fragments may be analyzed for composition, density, and isotopic ratios. While unusual compositions can spark interest, without a robust orbital trajectory linking the fragment to the event, composition alone cannot establish interstellar provenance.

- Check Peer-Reviewed Sources: Scientific conclusions are strongest when published in peer-reviewed journals. Claims found only in popular media, social essays, or videos should be cross-checked against available literature for methodology, data quality, and conclusions.

- Understand Natural Mimics: Solar System processes can produce apparent hyperbolic meteors through gravitational scattering by planets or fast cometary debris. Being aware of these mechanisms prevents overinterpretation of singular high-velocity events (Vokrouhlický et al., 2014).

- Maintain Scientific Skepticism: Extraordinary claims, such as an interstellar origin, require extraordinary evidence. Readers and researchers should remain cautious, prioritize data quality, and avoid relying solely on anecdotal reports or sensationalized media coverage.

By following these guidelines, both scientists and informed readers can critically assess claims of interstellar meteors, distinguishing between well-supported evidence and speculative interpretation, while remaining aligned with current peer-reviewed research and accepted scientific methodology.

Scientific Consensus

- No atmospheric meteoroid has been confirmed as interstellar.

- Most cataloged hyperbolic events are consistent with bound orbits when uncertainties are accounted for.

- Solar System dynamics can mimic interstellar signatures.

- Confirmed interstellar objects exist at larger scales (1I/’Oumuamua, 2I/Borisov), but atmospheric events have not yet met confirmation standards.

Conclusion

Scientific research continues to refine measurements of meteoroid trajectories, velocities, and fluxes. While interstellar meteoroids remain a compelling possibility, current peer-reviewed evidence does not confirm their detection in Earth's atmosphere. Claims highlighted in recent essays can stimulate discussion and hypothesis generation but must be evaluated with quantified uncertainties, multi-sensor verification, and robust population analysis.

References

- Musci, R., et al., “An Optical Survey for mm-Sized Interstellar Meteoroids,” DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.1110.5882

- Vidaurreta, A., et al., “The Influence of Meteor Measurement Errors on Heliocentric Orbits of Meteoroids,” DOI: 10.1016/j.pss.2020.104965

- Hajduková, M., et al., “No Evidence for Interstellar Fireballs in the CNEOS Database,” DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202449569

- Peña-Asensio, J. & Seligman, D., “The Interstellar Flux Gap: From Dust to Kilometer-Scale Objects,” DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.2511.01957

- Vokrouhlický, D., et al., “Gravitational Dynamics of Meteoroids,” DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2014.07.003