Written by: Astrophyzix Science Communication

Article type: Explainer, Current Science

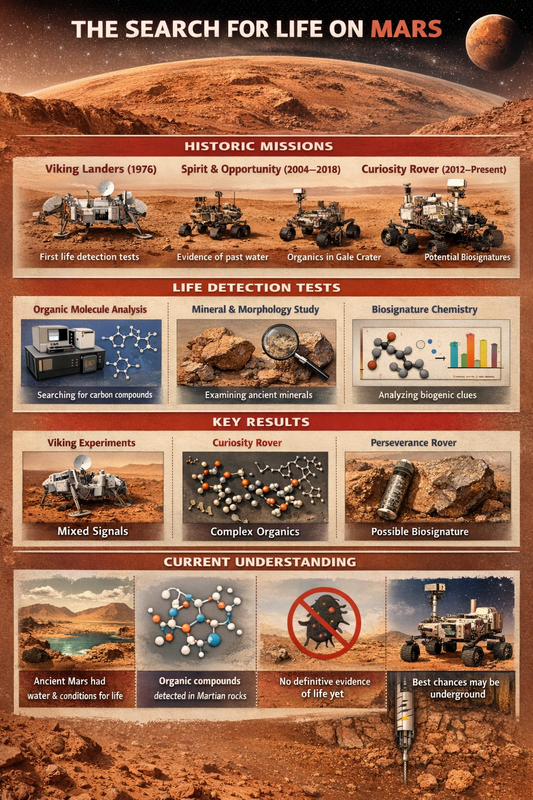

Introduction: The Search for Life on Mars

Mars is the most intensively studied world in the Solar System in humanity’s quest to determine whether life exists beyond Earth. Its ancient evidence for liquid water, diverse geological environments, and detectable organic compounds make it a leading target for astrobiology. Life detection involves identifying robust biosignatures—features that can only be explained by biology. The scientific challenge is to distinguish these from abiotic (non‑life) chemical and geological processes, which often produce similar signals.

Early Life‑Detection Missions

The first missions explicitly designed to search for life on Mars were NASA’s Viking landers in the 1970s.

Viking 1 & Viking 2 (1976)

The Viking missions carried four biology experiments per lander: Labeled Release (LR), Pyrolytic Release (PR), Gas Exchange (GEX), and a Gas Chromatograph–Mass Spectrometer (GCMS). While the LR tests yielded positive metabolic-like responses, the GCMS failed to detect indigenous organic molecules above its detection limit, leading the scientific community to interpret the results as abiotic soil chemistry rather than biology. Subsequent laboratory studies have shown that perchlorate in Martian soil could destroy organics during heating, complicating interpretation.

Shift to Habitability

Following Viking, Mars exploration shifted from direct life detection to characterizing environments capable of supporting life (“habitability”). Orbital and surface missions focused on identifying water, essential elements, and environmental history.

Modern Rovers & Biosignature Investigations

Curiosity Rover (2012–present)

NASA’s Curiosity carries instruments like Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) and CheMin for organic and mineralogical analysis. Curiosity has confirmed ancient freshwater lakes in Gale Crater and abundant rock-forming elements necessary for life. In 2025, scientists published the discovery of long-chain alkanes (decane, undecane, dodecane) in ancient mudstone, representing the largest organic molecules detected on Mars to date — molecules that may originate from fatty acids, common products of modern biochemistry.

Perseverance Rover (2021–present)

NASA’s Perseverance rover in Jezero Crater is optimized for astrobiology. It collects and caches rock cores for future Mars Sample Return. In 2025, peer-reviewed results indicate that a rock called “Cheyava Falls,” sampled from an ancient riverbed, contains chemical and textural features that are consistent with possible biosignatures (e.g., organic signatures plus mineralogical features like vivianite and greigite associated with biological processes on Earth). However, alternative abiotic formation mechanisms remain plausible.

Scientific Methods for Life Detection

Searching for life on Mars requires a combination of chemical, mineralogical, and geological analyses to identify potential biosignatures — indicators of past or present life. These methods must distinguish between features produced by living organisms and those resulting from purely chemical or geological processes. Over the decades, Mars missions have developed a suite of complementary approaches to achieve this goal.

- Organic Molecule Detection: Instruments such as the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) suite on Curiosity and the Mars Organic Molecule Analyzer (MOMA) planned for the ExoMars Rosalind Franklin rover use techniques like gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), pyrolysis, and laser desorption to identify organic molecules. SAM, for example, heats soil samples to release volatile organics, which are then separated and analyzed by mass spectrometry. The detection of complex organics such as long-chain hydrocarbons, thiophenes, and aromatic molecules indicates the presence of carbon-based chemistry that could be prebiotic or biological in origin.

- Mineralogy and Rock Context: Instruments like CheMin (X-ray diffraction) and Raman spectrometers examine the mineralogical composition of Martian rocks. Certain minerals, such as phyllosilicates (clays) and sulfates, form in the presence of water and can preserve organic molecules over geological timescales. By analyzing the mineral matrix alongside chemical data, scientists can evaluate whether organics are well-preserved and assess the environmental conditions in which they formed. On Earth, specific mineral-organic associations often correlate with microbial activity, providing a model for interpreting Martian data.

- Isotopic Analysis: Isotopic ratios of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and sulfur can help differentiate biotic from abiotic processes. For example, living organisms preferentially incorporate lighter isotopes of carbon (¹²C) over heavier ones (¹³C), creating a measurable fractionation pattern. Although current Mars rovers have limited isotopic resolution, instruments like SAM’s tunable laser spectrometer can measure isotopic ratios of methane and carbon dioxide, which may indicate potential biological activity in combination with other data.

- Imaging and Microscopy: High-resolution cameras (e.g., Mastcam, SuperCam, WATSON) capture detailed textures, layering, and potential microfossil-like features in rocks and sediments. On Earth, microscopic sedimentary structures, stromatolites, and mineralized microbial mats provide evidence of life; similar imaging on Mars helps scientists identify sites that warrant further chemical analysis or sample collection.

- Redox and Chemical Gradients: Life requires energy, typically obtained by exploiting chemical gradients. Instruments capable of detecting oxidized and reduced minerals (e.g., iron sulfides, magnetite, or ferric/ferrous iron ratios) allow scientists to reconstruct past redox conditions. Areas with preserved redox gradients indicate environments where microbial metabolism could have occurred.

- Subsurface Drilling and Sample Caching: Surface radiation and oxidative chemistry degrade organics rapidly. Drilling into sediments, as performed by Curiosity and Perseverance (up to 6 cm and 7 cm, respectively), accesses better-preserved layers where organics and potential biosignatures survive. Perseverance also caches rock cores for future Mars Sample Return, which will allow terrestrial laboratories to apply high-resolution mass spectrometry, electron microscopy, and isotopic analysis beyond the capabilities of in-situ instruments.

- Integration and Cross-validation: No single method can confirm life. Scientists combine multiple lines of evidence — organic chemistry, mineralogy, sedimentology, isotopes, and environmental reconstruction — to build a robust argument for or against past habitability and potential biosignatures. The synthesis of these datasets provides context and reduces false positives from abiotic chemical reactions that can mimic biological signatures.

Results So Far & Their Interpretation

No Confirmed Life Yet

Despite decades of exploration, no mission has conclusively detected current or past life on Mars. The strongest potential biosignatures come from organic and mineral patterns in ancient rocks, but abiotic explanations persist.

Habitability Confirmed

While direct evidence of life on Mars remains elusive, numerous missions have now confirmed that ancient Mars had environments capable of supporting life. Habitability refers to the presence of conditions suitable for life as we know it: liquid water, essential chemical elements (CHNOPS: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, sulfur), and energy sources to drive metabolism.

- Surface Water and Ancient Lakes: NASA’s Spirit and Opportunity rovers provided the first in-situ evidence of past water activity through the discovery of sedimentary rocks, sulfate-rich outcrops, and hematite concretions (“blueberries”) that form in aqueous environments. Curiosity further confirmed the existence of long-lived freshwater lakes in Gale Crater through the analysis of finely layered mudstones, cross-bedded sandstones, and mineral veins. These sediments suggest that water persisted on the surface for millions of years, providing a stable environment potentially capable of supporting microbial life.

- Essential Elements and Energy Sources: Analytical instruments such as SAM and CheMin aboard Curiosity revealed that ancient Martian rocks contain all the essential chemical elements for life. Additionally, redox gradients were identified in the mineralogical record, providing potential chemical energy sources. On Earth, such gradients are often exploited by microbial life, suggesting that ancient Mars may have offered not only a liquid medium but also energy for metabolic processes.

- Climate and Environmental Conditions: Orbital missions like the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Mars Odyssey mapped clay-rich regions and hydrated minerals, indicating that early Mars had a warmer and wetter climate suitable for sustaining liquid water. The presence of phyllosilicates (clays) suggests neutral to mildly alkaline water conditions, which are more favorable for life than highly acidic or saline environments. Later, sulfate-rich deposits indicate episodic, more acidic waters, which may have been less hospitable but still within the limits for certain extremophilic microbes.

- Subsurface Protection: While the surface environment today is exposed to high radiation and oxidative stress, ancient subsurface layers would have offered shielding from harmful UV light and preserved organics. This makes sedimentary layers in ancient lakebeds and river deltas particularly important targets for life detection, as they may contain chemical or even microfossil evidence of past microbial activity.

In summary, while no direct evidence of life has yet been found, multiple lines of geological, chemical, and mineralogical evidence confirm that ancient Mars was habitable. These findings provide the context in which organics and potential biosignatures detected by Curiosity and Perseverance could have formed and been preserved, making Mars a prime target in the search for past life.

Organics Are Present

Multiple missions to Mars have confirmed that organic molecules exist on the planet, ranging from simple volatiles to complex long-chain hydrocarbons. These findings are crucial because organic molecules are the building blocks of life as we know it, forming the backbone of amino acids, lipids, and nucleic acids. The presence of organics on Mars does not automatically indicate life; many can form through abiotic chemical processes, such as photochemistry in the atmosphere or hydrothermal reactions in the subsurface. However, the detection of preserved complex molecules in ancient rocks provides strong evidence that Mars had the raw ingredients necessary for life.

NASA’s Curiosity rover detected a range of organic molecules in 3.5–3.7 billion-year-old mudstones in Gale Crater. Instruments such as SAM (Sample Analysis at Mars) used gas chromatography–mass spectrometry to identify molecules including chlorobenzene, thiophenes, and long-chain alkanes (decane, undecane, dodecane). These complex organics are significant because they are larger and more chemically diverse than simple gases like methane, and they can be preserved in clay-rich sediments under anoxic conditions over billions of years.

In addition, Curiosity’s findings suggest that organics are not uniformly distributed but tend to persist in specific mineralogical contexts, particularly fine-grained mudstones that were deposited in ancient lakes. These environments likely provided protection from destructive factors such as ultraviolet radiation, perchlorates, and oxidizing conditions at the surface. The survival of these organics raises the possibility that, if life ever existed on Mars, its chemical signatures could also be preserved in similar sedimentary rocks.

The Perseverance rover is continuing this search in Jezero Crater, collecting samples from ancient river deltas and lakebeds. Preliminary analyses of rocks like “Cheyava Falls” indicate the presence of organic carbon embedded within mineral matrices such as iron sulfides and phosphates. These minerals can shield organics from degradation and, on Earth, are often associated with microbial metabolism, making them compelling targets for understanding potential biosignatures.

Overall, while organics are widespread and ancient on Mars, their origin — biotic or abiotic — remains undetermined. The study of these molecules provides critical insight into the planet’s chemical history and helps guide the selection of samples for the upcoming Mars Sample Return campaign, which may allow scientists to definitively test for evidence of past life using Earth-based laboratory instrumentation.

Multiple missions have now identified organic molecules on Mars, from simple volatiles to complex long-chain hydrocarbons. Their preservation suggests that organics can survive Martian surface conditions over geological timescales.

Biosignatures Remain Ambiguous

Features interpreted as potential biosignatures, such as the chemical signatures and textures in the “Cheyava Falls” sample, are compelling but not definitive. Alternative abiotic processes can often mimic biological effects, underscoring the need for returned samples and laboratory analysis.

Current Scientific Understanding

Today’s consensus within the planetary science community is that Mars presents strong evidence for past habitable environments and abundant organic chemistry, but direct evidence for life — extant or extinct — remains unconfirmed. Organic molecules and environmental conditions that could support microbial life are both observed, but life cannot yet be distinguished from non-biological chemical processes in situ. This is why Mars Sample Return and deep subsurface exploration are critical next steps.

Future Prospects

Mars Sample Return (MSR)

A multi-mission campaign between NASA and ESA aims to return Perseverance’s cached samples to Earth. Laboratory analysis of these samples with cutting-edge instrumentation may finally resolve whether Mars ever hosted life.

ExoMars Rosalind Franklin Rover

ESA’s ExoMars rover, planned for launch in 2028, will carry a drill capable of accessing subsurface samples up to ~2 m deep — a regime where organics and potential biosignatures are better preserved against radiation and oxidation.

Conclusion

While confirmed life on Mars remains elusive, the search has shifted from life detection experiments like those on Viking to a broader astrobiological framework integrating habitability, organic chemistry, and biosignature science. Discoveries of complex organics and potentially biologically relevant features in ancient rocks represent milestones in our understanding, but only with returned samples analyzed on Earth will the question of Martian life be definitively answered.

Sources

- Biemann et al., “Search for Organic and Volatile Inorganic Compounds in the Surface of Mars,” Science (1976)

- Kounaves et al., “Viking Mars Soil Chemistry Revisited,” PMC (2019)

- Freissinet et al., “Long-chain alkanes preserved in a Martian mudstone,” PNAS (2025)

- Vago et al., “ExoMars Rosalind Franklin Rover Astrobiology Objectives,” Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences (2023)

- Planetary Society, “Perseverance Finds Possible Biosignatures,” 2025